Inspiration from the bottom up

By Xiaowei Wang

Sr. Reny

The case of Yangguang village as a small experiment in regional economies is an inspiring example of what happens when technology becomes a tool rather than the solution for governance, and when technology is leveraged by communities rather than technologies managing communities, writes author Xiaowei Wang.

Technology is centred around promises and solutions and, while we may not often think of it, technology is also centred around places. Networks of software and hardware tools have promised to solve some of the most urgent problems, including questions of economic development throughout the world. At the heart of these development questions, rural places in the world have long been positioned as backward in time, and that they need to be ‘brought forward’ to the modern era by the makers and builders of technology in cities. With such top-down planning, we are missing an opportunity to strengthen and centre the needs of rural communities through the use technology as a tool rather than a form of governance.

In Chinese, the term ‘shanzhai’ means mountain stronghold, and it’s a word that has been long used to describe the practice of copycat technologies. In its newest form, as the director of Shenzhen Open Innovation Lab, David Li, and scholar Silvia Lindtner have described, new shanzhai is a form of extreme open source. Originally created as a response to those from mountain strongholds who couldn’t afford name-brand electronics, new shanzhai stands as a form of extreme open source in contrast to the highly corporate form of tech that has now overtaken the West. Embedded in new shanzhai is the need for right to repair and making technology accessible as a tool for all, not just those who can afford expensive iPhones, as well as the need for community-driven technology. The ethos of shanzhai is inherently bottom-up, rather than top-down.

“The ethos of shanzai is inherently bottom-up”

Xiaowei Wang

In Yangguang village, a few hours outside of Guangzhou, a small rice farming village is demonstrating a shanzhai economy in action. In 2018, a visit to the village showed a strong local economy centred around organic rice farming, facilitated by the cooperative Rice Harmony. The practices of the village emerged when farmers noticed that their soil was becoming less and less fertile using more ‘modern’ techniques of chemical fertilizers and pesticides. In response, they promptly switched to an organic rice farming technique, and changed the governing structure of their village so that farmers no longer had contiguous rice paddies.

As a result, farmers became incentivised to care for their paddies with the collective in mind. The agricultural machinery available on the market was also geared towards larger tracts of land, and so farmers throughout the village created their own machines to turn the soil as needed. To get their products to market, farmers sold their rice and rice wine using mobile payment and the store function on WeChat.

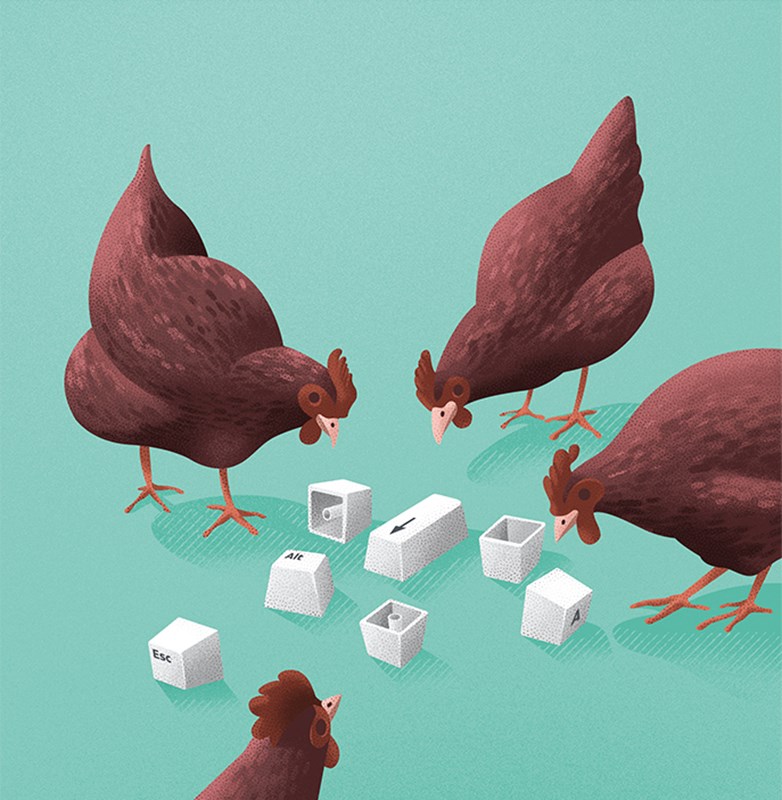

Contrasted against the success of Yangguang village is the GoGo Chicken project, which was a top-down initiative with the Shanghai-based technology company, Lianmo Keji (Shanghai OpenTrust company). While the Rice Harmony project continues on, the GoGo Chicken project began with much media fanfare and instead fizzled out after its first year.

These chickens had a chicken ‘FitBit’ of sorts attached to their legs, monitoring how many steps they took, and using blockchain to address food safety and provenance issues, guaranteeing the chickens were certifiably free-range. The blockchain that stored this data was an enterprise blockchain, to which the public did not have access. Given the high costs of this seemingly innovative technology, the chickens were extremely expensive, making food safety and provenance available for upper-middle class urbanites willing to pay such premiums.

The contrasts in these two approaches is a reminder that technology is ultimately a tool, and there is no one-size-fits-all solution. It is also a reminder that despite the internet possessing the narrative of a dematerialised world, emerging internet-enabled technologies are more material than ever. During the pandemic, as some people have shifted towards working from home, the data centres that support this new landscape are located throughout the rural regions of the world. The electricity that runs those data centres and the metals that form the hardware inside those computer servers also depend on rural extraction.

Through the pandemic, we’ve also experienced supply chain anxieties across the world along with shipping delays — these have included food supply chain anxieties as well. And while technology has enabled our current landscape of globalised, industrial agriculture, there remains enormous potential at the intersection of supporting small scale farming and regional economies. In fact, industrial agriculture is one of the leading causes of global greenhouse gas emissions, reminding us that the question of how we will live in cities is also a question for the countryside. As many of us have had to stay in one place during the pandemic, the question of local and regional scales became more important than ever.

When we talk about growth and development, it is clear that we are living in an interconnected world, between the rural and the urban, where the city is inextricably connected to the countryside whether through the flows of data or through food, land and labour.

The case of Yangguang village as a small experiment in regional economies is an inspiring example of what happens when technology becomes a tool rather than the solution for governance, when technology is leveraged by communities rather than technologies managing communities. Rural economies do not exist as anomalies in our world, but instead they truly enable the economic growth that we see in cities today. We must change not only the way we build technology but the ways we use it within policy and economic development.

It is only then we can arrive at a sustainable future with technology for all, not just for the few.